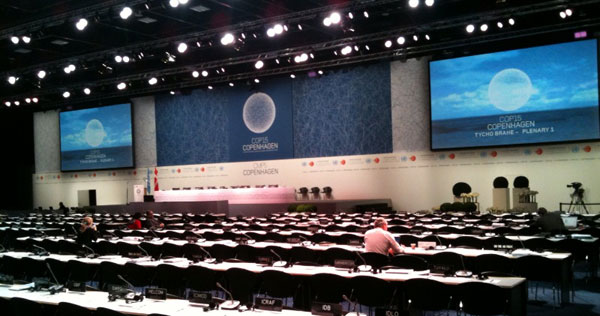

Today I spent my morning in the Bella Center, where the main conference is taking place, for the first time. It may also be the last time. Reports say that there are 45,000 people now registered, but capacity is only 15,000. Starting tomorrow admission to the Bella Center will be further restricted and delegates will require a second, rationed pass to get in. (My NGO has 19 passes to share between 89 delegates.)

Today I spent my morning in the Bella Center, where the main conference is taking place, for the first time. It may also be the last time. Reports say that there are 45,000 people now registered, but capacity is only 15,000. Starting tomorrow admission to the Bella Center will be further restricted and delegates will require a second, rationed pass to get in. (My NGO has 19 passes to share between 89 delegates.)

You might expect that a planning failure of that magnitude would be greeted with frustration, but so far I’ve witnessed very little. Instead, everyone I’ve met seems determined to contribute as positively to the process as they can, whether within the official conference or without. We’ll see how long that lasts, however. We’re talking about people from well-established NGOs who have traveled from all over the world to be here and who have gone through the proper registration process only to be turned away. Fewer observers will be admitted every day this week. According to one report by Friday only 90 people from NGOs will be let in. 90. Out of tens of thousands. It could get tense.

Climate change you can believe in

The context of the conversation that’s taking place in Copenhagen is entirely different from that in North America. Instead of arguing about if climate change is a real and serious concern or predicting future consequences if we don’t act, the narrative here is that dangerous climate change is already a reality.

At a powerful ecumenical service yesterday led by Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu and the Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, three choirs from three corners of the Earth brought with them symbols of how climate change is affecting their lives: rocks uncovered from melting glaciers in Greenland, dead, bleached coral from the Pacific ocean, and dried up maize from Africa.

Today I listened to a man from the island nation of Tuvalu, which is emerging at this meeting as a symbol of why we must act. The highest point in Tuvalu is 4.5 meters above sea level. In other words, unless we aggressively reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, this nation will slip beneath the waves. Negotiators from Tuvalu have been strongly pushing for tough, binding targets in plenary, and the tiny state has captured the imagination of many of the NGO delegates, particularly the youth.

Today I listened to a man from the island nation of Tuvalu, which is emerging at this meeting as a symbol of why we must act. The highest point in Tuvalu is 4.5 meters above sea level. In other words, unless we aggressively reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, this nation will slip beneath the waves. Negotiators from Tuvalu have been strongly pushing for tough, binding targets in plenary, and the tiny state has captured the imagination of many of the NGO delegates, particularly the youth.

Through this lens, the Canadian government’s pathetic non-participation in the negotiations is seen as not just embarrassing, but cruel. The world’s poorer countries believe they are already suffering, and that people are already dying, because of the actions of the world’s richer countries. For them it is as if the United States, Canada, and Europe are turning a giant tap that slowly drowns them while they cry out in vain. The immorality becomes blatant and blaring. And yet they continue to chose hope over anger; it’s remarkable.

Explaining Canada

One thing that does unite representatives from European countries and the countries of the south is their complete shock, dismay, and confusion at the role that Canada is playing. Whereas most developed countries are promising emissions reductions in the range of 20-40% below 1990 levels, Canada is offering a 3% reduction. Whenever I’ve told that to someone they’ve assumed they’ve misheard me; it’s unbelievably poor.

One thing that does unite representatives from European countries and the countries of the south is their complete shock, dismay, and confusion at the role that Canada is playing. Whereas most developed countries are promising emissions reductions in the range of 20-40% below 1990 levels, Canada is offering a 3% reduction. Whenever I’ve told that to someone they’ve assumed they’ve misheard me; it’s unbelievably poor.

So then I get into conversations about the fact that the majority of Canadians support action, that the vast majority of Canadians voted for parties that support taking action, etc. Not that that’s much consolation. Still, I feel like it’s one of my more important roles to help people understand how Canada’s gone so wrong, and how so many of us are working to make it better.

Waiting for Obama

According to Bill McKibben of 350.org, who spoke earlier today at Klimaforum, the parallel “people’s summit,” there is a team from MIT here in Copenhagen with powerful computers. Their job, at the end of each day, is to look at all of the commitments that countries have offered that day and calculate how many parts per million of carbon that would mean for the atmosphere. Before the industrial revolution that number was around 280ppm, anything above 350ppm is unsafe, and today we’re at approximately 380ppm. According to the MIT projections, if an agreement were signed today as-is we’d be on our way above 700ppm. “If that isn’t literally hell,” McKibben said, “it would look a lot like it.”

According to Bill McKibben of 350.org, who spoke earlier today at Klimaforum, the parallel “people’s summit,” there is a team from MIT here in Copenhagen with powerful computers. Their job, at the end of each day, is to look at all of the commitments that countries have offered that day and calculate how many parts per million of carbon that would mean for the atmosphere. Before the industrial revolution that number was around 280ppm, anything above 350ppm is unsafe, and today we’re at approximately 380ppm. According to the MIT projections, if an agreement were signed today as-is we’d be on our way above 700ppm. “If that isn’t literally hell,” McKibben said, “it would look a lot like it.”

In other words, we’ve got a long way to go. And so, a lot of hope rests on the arrival of U.S. President Barack Obama on Friday. At lunch yesterday we quipped, “when he walks into a room everything just gets fixed, right?” The statement was 70% joke and 30% willful delusion. “Oh, you’re Canadian,” our American friend said. “You still believe that. We know better.”

Back at Klimaforum, McKibben predicted that Obama would likely make a beautiful speech, but that no speech was beautiful enough to alter the scientific and moral imperative to begin reducing global greenhouse gas emissions by 2015 at the latest. “The laws of nature will not be swayed by Barack Obama’s oratory,” he said, “but they would be swayed by his action.”

All pictures by me and my iPhone